Vasospasm refers to the sudden constriction of blood vessels, which leads to reduced blood flow and can result in significant clinical complications. This phenomenon is particularly critical when it occurs in the cerebral arteries, often following a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and can cause delayed cerebral ischemia. However, vasospasm can affect various parts of the body and can be triggered by different factors. Understanding the underlying causes is essential for effective prevention and treatment. This article explores the five main causes of vasospasm.

5 Main Causes of Vasospasmb

1. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

Overview

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is one of the most significant and well-documented causes of vasospasm, particularly in the brain. SAH refers to bleeding into the subarachnoid space—the area between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater surrounding the brain. This condition is often caused by a ruptured aneurysm, although trauma can also lead to SAH.

Pathophysiology

Following SAH, blood breaks down and releases various substances, including hemoglobin, which can irritate the cerebral arteries. This irritation prompts the release of vasoactive substances such as endothelin-1 and decreases the availability of nitric oxide, a vasodilator.

Consequently, the smooth muscle in the blood vessel walls contracts, leading to vasospasm.

SEE ALSO: Where Is The Right Coronary Artery Located in The Heart?

Clinical Impact

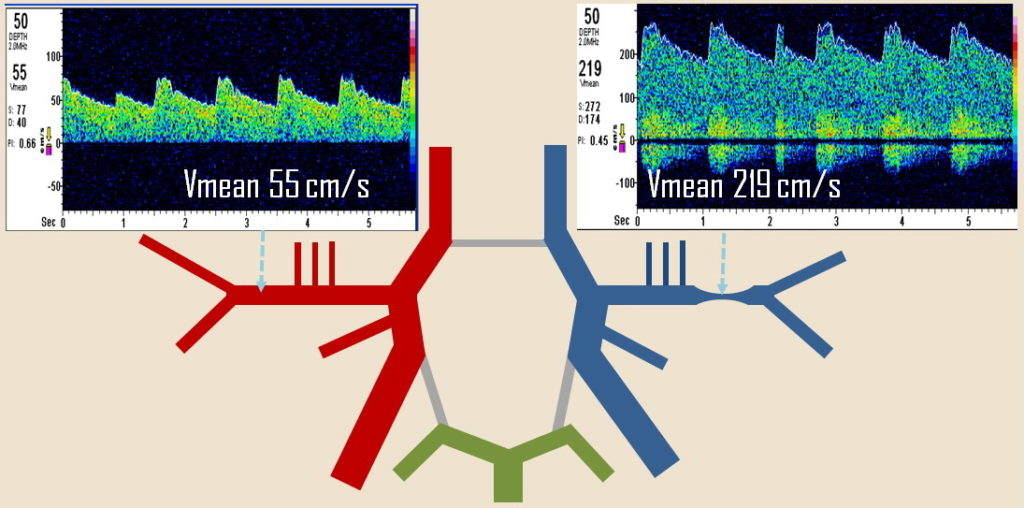

Cerebral vasospasm typically occurs between 3 to 14 days after the initial hemorrhage and can cause delayed cerebral ischemia, leading to stroke-like symptoms, neurological deficits, and in severe cases, death.

The management of SAH-related vasospasm involves nimodipine administration, maintaining adequate blood pressure and volume status, and in some cases, endovascular treatments such as balloon angioplasty or intra-arterial vasodilators.

2. Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS)

Overview

Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) is a condition characterized by a sudden, severe, thunderclap headache and multifocal segmental narrowing of the cerebral arteries that resolves within three months. Although the exact cause of RCVS is unknown, it is believed to be triggered by various factors.

Triggers

Common triggers of RCVS include:

Medications: Certain drugs, particularly those that affect vascular tone, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), triptans (used for migraines), and sympathomimetic agents (used in decongestants and weight loss), can precipitate RCVS.

Postpartum State: Hormonal changes and stress related to childbirth are significant risk factors.

Illicit Drugs: Cocaine, amphetamines, and cannabis have been linked to RCVS.

Physical Exertion and Emotional Stress: Intense physical activity or acute emotional stress can also trigger RCVS.

Pathophysiology

RCVS is characterized by transient abnormalities in the regulation of cerebral arterial tone, leading to reversible vasoconstriction. The exact mechanisms remain unclear, but a temporary disturbance in the balance between vasoconstricting and vasodilating factors in the brain is suspected.

Clinical Impact

Patients with RCVS typically present with severe, sudden-onset headaches, sometimes accompanied by focal neurological deficits or seizures. The condition is usually self-limiting, but complications such as ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke can occur. Management focuses on symptomatic treatment of headaches and avoiding known triggers.

3. Coronary Artery Spasm (CAS)

Overview

Coronary artery spasm (CAS), also known as Prinzmetal’s angina or variant angina, involves a temporary, sudden narrowing of the coronary arteries, leading to reduced blood flow to the heart muscle. This condition can cause chest pain and, if prolonged, myocardial infarction (heart attack).

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanisms underlying CAS are not fully understood, but several factors are implicated:

Endothelial Dysfunction: Impairment of the endothelium’s ability to produce vasodilators like nitric oxide can lead to an imbalance favoring vasoconstriction.

Smooth Muscle Hyperreactivity: Abnormalities in the smooth muscle cells of the coronary arteries can cause an exaggerated contractile response.

Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance: Overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system or underactivity of the parasympathetic nervous system can contribute to CAS.

Triggers

Common triggers of CAS include:

Stress and Anxiety: Emotional stress can provoke CAS.

Cold Exposure: Cold weather can trigger vasospasm in susceptible individuals.

Medications and Drugs: Cocaine and certain medications, such as ergotamine, can induce CAS.

Clinical Impact

CAS can present with chest pain at rest, often occurring in the early morning hours. Unlike typical angina, it is not necessarily related to physical exertion. The diagnosis is confirmed through coronary angiography showing transient narrowing of the coronary arteries, and the administration of vasodilators like nitroglycerin can help alleviate symptoms.

Treatment focuses on calcium channel blockers and nitrates to prevent spasms and manage symptoms.

4. Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Overview

Raynaud’s phenomenon is a condition characterized by episodic vasospasm of the small arteries, typically in the fingers and toes, in response to cold or stress. It can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to other conditions, such as scleroderma or lupus.

Pathophysiology

Raynaud’s phenomenon involves exaggerated vasoconstrictive responses to cold temperatures or emotional stress. The exact mechanisms include:

Neurovascular Dysfunction: Abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system regulation of blood flow.

Endothelial Dysfunction: Reduced production of vasodilators like nitric oxide.

Microvascular Changes: Structural changes in the microvasculature can contribute to vasospasm.

Triggers

Common triggers of Raynaud’s phenomenon include:

Cold Exposure: Even mild cold can precipitate an episode.

Emotional Stress: Anxiety and stress can also trigger vasospasm.

Clinical Impact

During an episode, affected digits turn white (due to lack of blood flow), then blue (due to prolonged lack of oxygen), and finally red (as blood flow returns). This can cause pain, tingling, and numbness.

Severe cases can lead to digital ulcers or gangrene. Management includes lifestyle modifications to avoid triggers, calcium channel blockers, and in severe cases, surgical interventions.

5. Medication-Induced Vasospasm

Overview

Certain medications can cause vasospasm as a side effect. This includes both prescription and over-the-counter drugs.

Common Medications

Ergot Alkaloids: Used for migraine treatment, these can cause significant vasoconstriction.

Triptans: Another class of migraine medications, triptans can lead to coronary and cerebral vasospasm.

Chemotherapeutic Agents: Some drugs used in cancer treatment, such as 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin, can cause vasospasm.

Sympathomimetics: Medications containing ephedrine or pseudoephedrine, often found in decongestants, can induce vasospasm.

Pathophysiology

Medication-induced vasospasm occurs through various mechanisms, depending on the drug involved. These mechanisms may include:

Direct Vasoconstrictive Action: Some medications directly stimulate vasoconstriction.

Endothelial Damage: Certain drugs can damage the endothelial lining of blood vessels, reducing the production of vasodilators.

Sympathetic Nervous System Activation: Some medications increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, leading to vasoconstriction.

Clinical Impact

The clinical presentation of medication-induced vasospasm varies depending on the affected vessels. Symptoms can range from chest pain and ischemia in coronary artery spasm to severe headaches in cerebral vasospasm. Management involves discontinuing the offending medication and treating the symptoms with appropriate vasodilators.

Conclusion

Vasospasm is a complex and multifaceted condition with various underlying causes. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, coronary artery spasm, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and medication-induced vasospasm represent the primary culprits. Understanding these causes is crucial for timely diagnosis and effective management. Each cause has distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical presentations, and treatment strategies.