Heart failure is a complex and progressive condition that affects millions of people worldwide. As the heart becomes less effective at pumping blood, various treatment strategies are employed to manage the symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life. Among these treatments, the use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a significant consideration. However, the decision to implant an ICD is not made lightly and is typically reserved for specific stages of heart failure where the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) is heightened. This article will explore the relationship between the stages of heart failure and the need for a defibrillator, providing insights into when this critical intervention becomes necessary.

Understanding Heart Failure Stages

Heart failure is classified into different stages by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). These stages, labeled A through D, represent the progressive nature of heart failure, from high risk of developing heart failure to advanced heart failure. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) also classifies heart failure based on functional limitations, ranging from Class I (no symptoms) to Class IV (severe symptoms).

Stage A: At risk of heart failure but without structural heart disease or symptoms.

Stage B: Structural heart disease is present but without symptoms of heart failure.

Stage C: Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of heart failure.

Stage D: Refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions.

The Role of Defibrillators in Heart Failure

What is a Defibrillator?

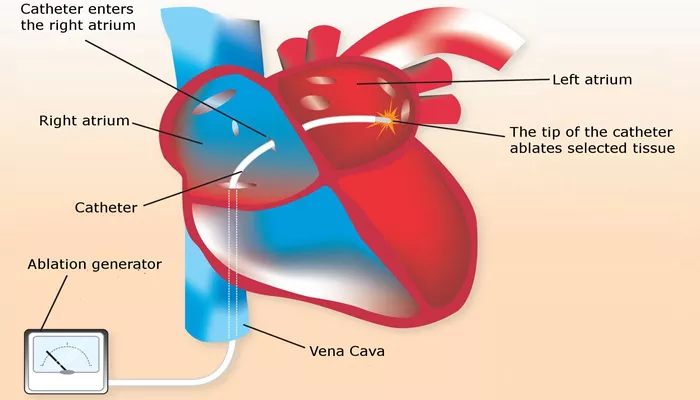

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a small device placed under the skin, typically near the collarbone, which continuously monitors the heart’s rhythm. If it detects a life-threatening arrhythmia, such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, the ICD delivers an electrical shock to restore a normal heart rhythm. This ability to prevent sudden cardiac death makes ICDs a crucial component in the management of heart failure in select patients.

SEE ALSO: What Do Heart Failure Nails Look Like?

Indications for ICD in Heart Failure

The decision to implant an ICD in heart failure patients is guided by specific clinical criteria. These criteria are primarily based on the stage of heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and the presence of arrhythmias. The LVEF is a key measure of how well the heart pumps blood with each contraction, with a normal LVEF ranging from 55% to 70%. A reduced LVEF, particularly below 35%, is associated with a higher risk of sudden cardiac death, which is a key consideration in the use of an ICD.

Stage C Heart Failure and ICDs

ICDs are most commonly considered in patients with Stage C heart failure, where there is structural heart disease with current or previous symptoms. According to guidelines, an ICD is recommended for patients with:

An LVEF of 35% or less, despite optimal medical therapy, and who have had a prior myocardial infarction (heart attack).

An LVEF of 30% or less, regardless of prior myocardial infarction, but with symptomatic heart failure (NYHA Class II or III).

A history of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, even if their LVEF is above 35%.

These criteria underscore the importance of the ICD in preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with significant myocardial damage and a high risk of malignant arrhythmias.

Stage D Heart Failure and ICDs

In Stage D heart failure, where patients have advanced, refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions, the role of ICDs becomes more nuanced. While these patients are at high risk for arrhythmias, the overall prognosis is poor, and the benefits of ICD implantation must be weighed against the potential for prolonged suffering. In some cases, especially where a patient is being considered for a heart transplant or left ventricular assist device (LVAD), an ICD may still be appropriate.

However, for patients who are not candidates for these interventions and who may be nearing end-of-life care, the use of an ICD might be reconsidered in favor of comfort-focused care.

The Timing of ICD Implantation

Primary Prevention vs. Secondary Prevention

ICDs are used both for primary prevention (to prevent sudden cardiac death before it occurs) and secondary prevention (after a life-threatening arrhythmia has occurred). The stage of heart failure and the specific clinical circumstances will determine whether an ICD is used for primary or secondary prevention.

Primary Prevention: Patients with Stage C heart failure and a reduced LVEF (≤35%) are the primary candidates for ICDs for primary prevention. These patients are at high risk for sudden cardiac death even if they have not yet experienced a life-threatening arrhythmia.

Secondary Prevention: Patients who have already survived a life-threatening arrhythmia (e.g., ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) are candidates for ICD implantation regardless of their LVEF. This is often seen in patients with both Stage C and Stage D heart failure.

Optimal Timing for ICD Implantation

The timing of ICD implantation is crucial for maximizing its benefits. It is generally recommended that patients be on optimal medical therapy for at least three months before considering an ICD, as medications and other treatments can sometimes improve LVEF and reduce the need for an ICD. For patients who remain symptomatic with an LVEF of 35% or less despite optimal medical therapy, ICD implantation should be considered to prevent sudden cardiac death.

Risks And Considerations

Potential Risks of ICD Implantation

While ICDs are life-saving devices, their implantation is not without risks. Complications can include:

Infection: Infection at the implant site can occur, sometimes necessitating the removal of the device.

Lead Problems: The leads, which connect the ICD to the heart, can sometimes dislodge or fracture, leading to inappropriate shocks or device malfunction.

Inappropriate Shocks: ICDs can sometimes deliver shocks when they are not needed, which can be distressing for the patient.

Psychological Impact: The presence of an ICD and the potential for receiving a shock can cause anxiety and affect the patient’s quality of life.

Conclusion

The need for a defibrillator in heart failure patients is closely tied to the stage of heart failure, particularly in those with Stage C heart failure and a significantly reduced ejection fraction. An ICD is a powerful tool in preventing sudden cardiac death, but its use must be carefully considered, balancing the potential benefits with the associated risks and the patient’s overall prognosis. As heart failure progresses, the decision to implant an ICD becomes more complex, especially in advanced stages where the focus may shift to comfort and quality of life. Ultimately, the timing and appropriateness of ICD implantation require a personalized approach, with ongoing evaluation and shared decision-making between the cardiologist and patient.