Research has shown that animal models of atherosclerosis often rely on inducing high cholesterol levels to study the disease’s progression. In these models, the size of arterial plaques correlates with cholesterol levels in the bloodstream.

Traditionally, these models have focused on maintaining high cholesterol levels later in the animals’ lives. However, this approach does not reflect the lifelong variations in cholesterol exposure experienced by humans.

To better understand this, researchers developed a new model that introduces early intermittent hyperlipidemia in mice while keeping overall cholesterol exposure equivalent to traditional models with sustained high cholesterol.

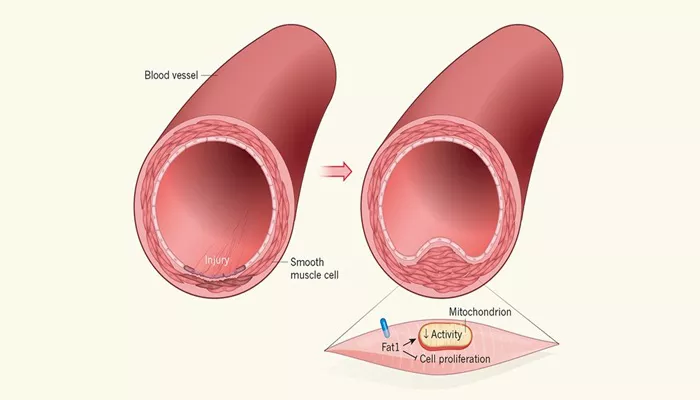

In a series of experiments, Ldlr−/− male mice were fed either a continuous Western diet (cWD) or an early intermittent Western diet (iWD). The study found that plasma cholesterol levels and other physiological markers, such as heart rate, weight, and blood pressure, were similar between the two groups. However, the mice on the early intermittent diet exhibited significantly larger atherosclerotic plaques compared to those on the continuous diet.

This finding was consistent across both male and female mice, although the increase in plaque size was more pronounced in females.

The plaques in the iWD mice were not only larger but also showed increased inflammation and necrosis. These plaques were characterized by a higher number of macrophages and T cells, as well as larger necrotic cores, indicating altered plaque healing and increased disease severity.

The study also investigated the role of gut microbiota, which can be influenced by the Western diet and may affect atherosclerosis development. After six weeks on their respective diets, the gut microbiota composition differed slightly between the two groups.

Antibiotic treatment reduced the acceleration of atherosclerosis in the iWD-fed mice but did not completely prevent it, suggesting that the microbiota plays a limited role in this model.

Additionally, the researchers examined adaptive immunity by studying Ldlr−/−/Rag2−/− mice, which lack T and B cells.

These mice still showed accelerated atherosclerosis under the iWD diet, indicating that innate immune responses are more critical in this process.

Further analysis through RNA sequencing revealed significant changes in macrophage gene expression, particularly concerning autophagy and efferocytosis—processes vital for maintaining plaque stability. The findings indicated that early intermittent hyperlipidemia led to reduced autophagy in macrophages, contributing to the formation of larger, more necrotic plaques.

In conclusion, this study highlights that early intermittent hyperlipidemia is a significant driver of atherosclerotic plaque development, even when total cholesterol exposure is similar to that seen in late hyperlipidemia. Early-life exposure to high cholesterol levels greatly influences atherosclerosis progression, explaining the strong connection between early cholesterol fluctuations and later cardiovascular events.

The research underscores the importance of managing cholesterol levels early in life to mitigate long-term cardiovascular risks. Impaired autophagy and efferocytosis pathways in arterial macrophages, particularly in resident-like macrophages, are identified as key factors contributing to accelerated atherosclerosis. Early cholesterol management is crucial for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease in the future.