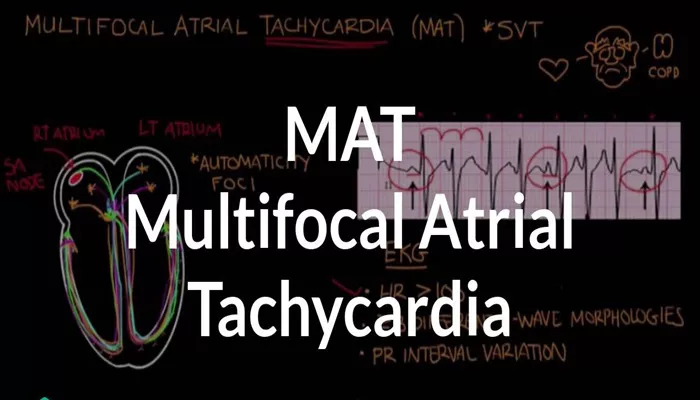

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is a type of supraventricular tachycardia characterized by rapid heart rates originating from multiple ectopic foci in the atria. This condition is often seen in patients with underlying pulmonary diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but can also occur in other contexts, including electrolyte imbalances and acute infections.

Pathophysiology of MAT

In MAT, the heart rate exceeds 100 beats per minute, and the rhythm is irregular. The presence of multiple ectopic foci leads to varying P-wave morphologies on an electrocardiogram (ECG), which is a hallmark of this arrhythmia. Unlike atrial fibrillation, where the rhythm is chaotic and disorganized, MAT maintains a more organized yet rapid rhythm due to the simultaneous firing of multiple atrial pacemakers.

Is MAT Dangerous?

While MAT itself is not usually classified as dangerous, its implications can be serious due to its association with other health conditions. Here are key points regarding its potential dangers:

Underlying Health Risks: Patients with MAT often have other significant health issues that can complicate their overall condition. For example, lung diseases like COPD can lead to inadequate oxygenation, exacerbating cardiac issues.

Sustained Episodes: When MAT episodes are prolonged or frequent, they can lead to complications such as:

Cardiomyopathy: Prolonged tachycardia can weaken the heart muscle over time.

Heart Failure: If the heart cannot effectively pump blood due to rapid rates, it may lead to heart failure.

Stroke Risk: Although less common than in atrial fibrillation, there remains a risk for thromboembolic events if blood flow is significantly compromised.

Management Challenges: Treatment for MAT often focuses on addressing the underlying conditions rather than the arrhythmia itself.

This means that if associated conditions are not well-managed, MAT may persist or worsen.

see also: Why Does Atrial Flutter Occur?

Clinical Significance

MAT can be dangerous for several reasons:

Increased Heart Rate: The rapid heart rate can lead to decreased cardiac output, particularly in patients with compromised cardiac function.

Underlying Conditions: MAT often indicates the presence of significant underlying health issues, such as heart failure or severe lung disease, which can complicate management and prognosis.

Potential for Progression: If left untreated, MAT may progress to more severe arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.

Management of MAT involves addressing the underlying causes, controlling the heart rate, and sometimes using antiarrhythmic medications. In some cases, catheter ablation may be considered if the arrhythmia is persistent and symptomatic.

Rebuilding Gingival Bone Loss

Gingival bone loss occurs when the supporting bone around teeth deteriorates due to periodontal disease or other factors.

Restoring this bone is essential for maintaining dental health and preventing tooth loss. Below are various methods for rebuilding gingival bone loss.

What Is Bone Loss?

Bone loss around teeth typically results from untreated periodontal disease. Bacteria infect the gum tissue, leading to inflammation and destruction of the supporting structures. As the disease progresses, pockets form between the gums and teeth, allowing more bacteria to flourish and further exacerbate bone loss.

Treatment Options for Bone Regeneration

Scaling and Root Planing: This non-surgical procedure involves deep cleaning below the gum line to remove plaque and tartar. It helps reduce inflammation and allows gums to reattach to teeth.

Bone Grafting: This surgical procedure replaces lost bone with graft material. The graft can be derived from:

Autografts: Bone taken from another site in the patient’s body.

Allografts: Bone sourced from a human tissue bank.

Xenografts: Bone obtained from animals (usually bovine).

Alloplasts: Synthetic materials designed to promote bone growth.

Bone grafting acts as a scaffold for new bone formation and helps stabilize teeth.

Guided Tissue Regeneration (GTR): This technique involves placing a barrier membrane between the gum tissue and bone graft material.

The membrane prevents soft tissue from interfering with bone regeneration, allowing new bone to grow in areas that have been lost.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Therapy: PRP involves concentrating platelets from a patient’s blood to promote healing and tissue regeneration. When applied during surgical procedures like bone grafting, PRP can enhance recovery and improve outcomes.

Soft Tissue Grafting: If there is significant gum recession along with bone loss, soft tissue grafts may be necessary to cover exposed tooth roots and improve aesthetics.

Surgical Procedures for Advanced Cases

In cases of severe periodontal disease where significant bone loss has occurred:

Flap Surgery (Pocket Reduction Surgery): This procedure involves lifting back the gums to clean deeper areas around teeth and reshape damaged bone.

Sinus Lift Procedure: For upper jaw cases where there is insufficient bone height for implants, this procedure raises the sinus floor and adds graft material.

Post-Treatment Care

After undergoing any surgical procedure for bone regeneration, proper oral hygiene is crucial:

Maintain regular dental check-ups.

Follow prescribed oral care routines.

Avoid tobacco use which can impede healing.

Conclusion

Rebuilding gingival bone loss is essential for maintaining dental health and preventing tooth loss due to periodontal disease. Early intervention through non-surgical treatments like scaling and root planing can halt progression before surgical options become necessary. For those with advanced disease, surgical interventions such as bone grafting or guided tissue regeneration offer promising outcomes for restoring lost structures.

Related topics:

- Can Arrhythmia Cause Heart Attack?

- Can Stress Cause An Arrhythmia?

- How to Calm A Racing Heart Before Bed